The Heinsheimer daughters—Alice, Lina, Jennie, and Rosie, with their brother Siegfried—circa 1906. My grandmother Alice served as a nurse in the Eppingen Hospital, nursing German soldiers in World War I, and was subsequently matched with Sigmar Günzburger, a businessman from Freiburg im. Breisgau. When they married in 1920, she was 28, and he was 40. They quickly had three children: Norbert, Hanna (later known as Janine), and Trudi.

Sigmar served in the German Army in WWI. He is the second from the left in the front row.

The family lived in the beautiful medieval university town of Freiburg im Breisgau in the warm, southwest corner of Germany. Their home at Poststrasse 6 stood to the right of the Hotel Minerva.

The Nazi newspaper in Freiburg, Der Alemanne, declared war on Germany’s Jews on March 31, 1933. It announced an anti-Jewish rally to take place on the square of the city’s cathedral and directed German citizens to boycott Jewish-owned firms, among them the Günzburger Brothers steel and construction supply company.

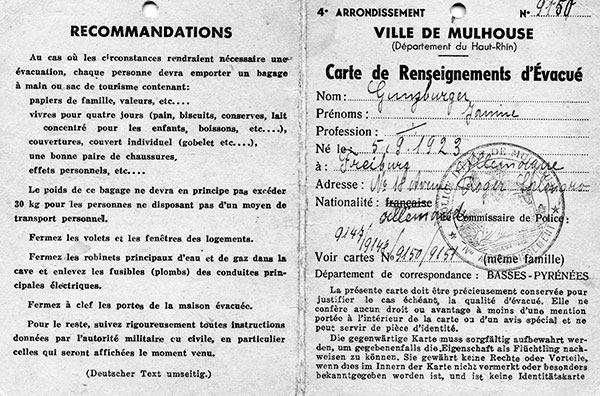

The evacuation card issued to Janine by the city of Mulhouse in 1939 in anticipation of a German invasion over the nearby border. The French population fled en masse from border regions, but for almost a year – a period termed the Phony War – no fighting started. Janine’s family moved to Gray, a small village that was occupied by German troops after France’s swift defeat in 1940, while Roland’s family settled in Villefranche, a town outside of Lyon, where he attended law school.

Janine (R) poses with Trudi and Norbert on the balcony of their Lyon apartment at 14, place Rambaud. It was in Lyon, part of the unoccupied zone, that Janine and Roland -- having first met in Alsace -- rediscovered one another, fell in love, and vowed to marry after the war.

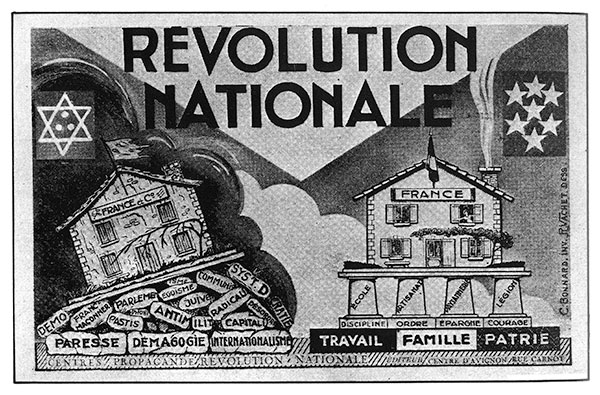

After France's fall to the Nazis, the collaborationist regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain imposed a new order called the Révolution Nationale that charged Jews, Communists, Freemasons, and the influences of laziness, drink, and egoism as being responsible for the country's humbling defeat.

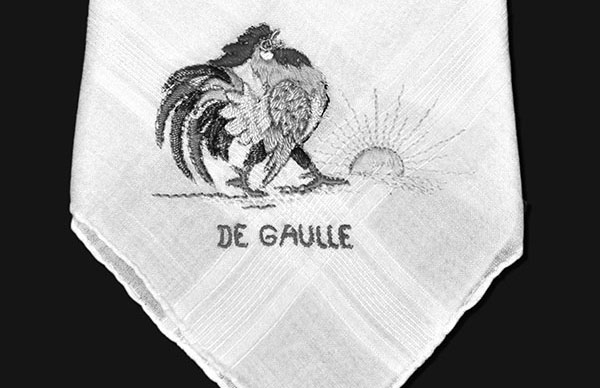

The brightly embroidered handkerchief that Roland gave to Janine at the pier in Marseille where she boarded the steamship Lipari on March 13, 1942, escaping France for Casablanca en route to Cuba. French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle was sentenced to death in absentia, but he organized opposition to Hitler from asylum in London.

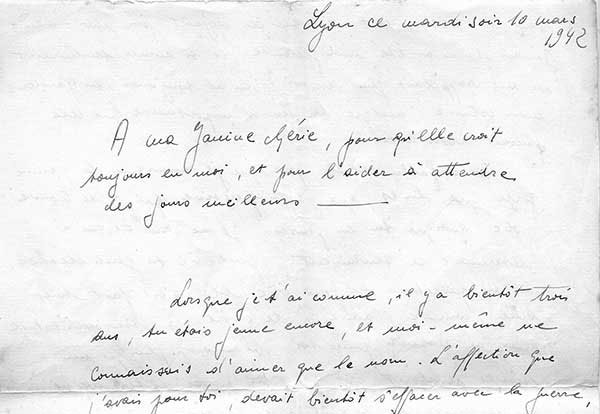

Roland’s parting letter to Janine was a twelve-page declaration of love, containing vows of love and pledges to marry after the war. It was confiscated by British officials who searched the refugee ship when it stopped in Jamaica, but she later retrieved it, waiting for her poste restante in Havana, and she treasured it always.

The steamship Lipari on which Janine's family escaped from Marseille to Casablanca -- the last ship to get out France in 1942 before the Nazis sealed off its ports for the duration of the war.

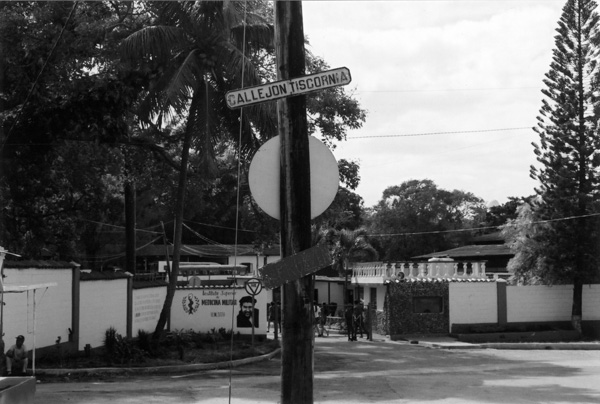

Information on the Cuban refugee detention camp of Tiscornia – where the Günzburgers and hundreds of other Jewish refugees were held for months behind gates – was hard to find. As of 2004, the street sign on Callejón Tiscornia provided the only indication of where the camp stood. The site had become the home of Cuba’s Instituto Superior de Medicina Militar, where armed guards barred entry.

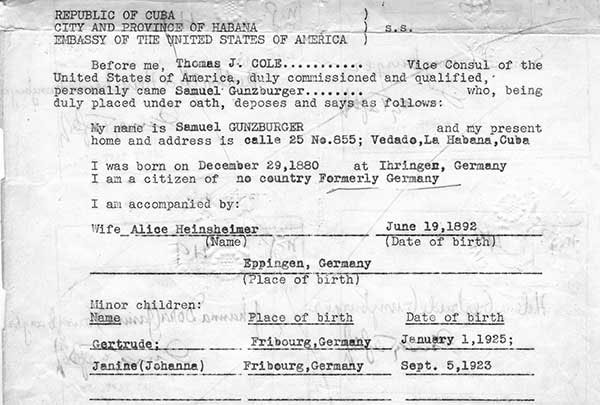

Visas to enter the United States were extremely difficult to obtain for Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Europe, and only 10 percent of those technically slotted for them were ever awarded. Denationalized by the German government, Jews like Sigmar lacked passports and eventually needed affidavits like this one, dated July 19, 1943, to enter the United States.

Leonard Laurence Maitland was a 28-year-old graduate of New York University’s School of Engineering when, just released from the United States Merchant Marine, he met Janine.

Her father having intercepted Roland’s efforts to find her, Janine finally agreed to marry someone else, Leonard Maitland. "Because God Made You Mine” was the bridal march at their wedding in Sea Cliff, Long Island on Monday, July 28, 1947.

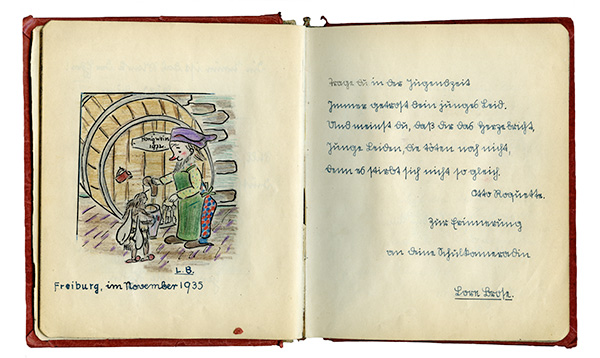

In the archaeology of love, Janine's childhood autograph book, left behind in Europe when she fled, provided Leslie with an important clue that she was on the right track in seeking to learn the fate of Roland.

As part of a project that has already memorialized more than 30,000 victims of Nazism throughout Europe, in 2005 the artist Gunter Demnig imbedded these two Stolpersteine or "stumbling stones" in the sidewalk in front of the family's former Freiburg home. The inscriptions translate as follows: "Here lived Samuel Sigmar Günzburger, born in 1880, fled in 1938, survived five years of flight." "Here lived Alice Berta Günzburger, née Heinsheimer, born in 1892, fled in 1938, survived five years of flight."