On January 27, 1945, Soviet troops liberated the Nazi concentration camp of Auschwitz and its last 7,000 feeble, ill, or dying prisoners. Tens of thousands of others had been forced on death marches in preceding weeks, as the S.S. furiously tried to empty the camp before the Allies discovered the unimaginable cruelty that had reigned within its gates. By then, more than a million captives had been murdered there. Sixty years later, the United Nations would designate January 27 to serve annually as International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In Israel, however, as in most Jewish communities, the memorial occasion is more widely observed on Yom HaShoah, which occurs a week after the end of Passover and is linked to the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Its precise yet variable date each spring falls on the 27th day of the month of Nissan, as determined by the lunar, Hebrew calendar.

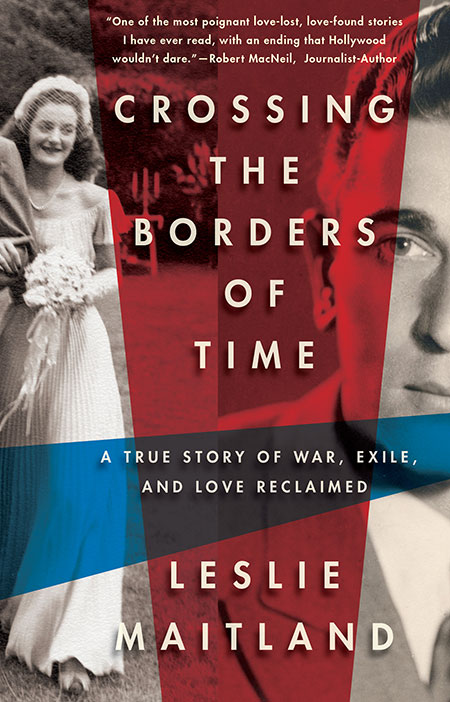

Curiously, these two dates add to a long list of other pivotal events that happened on the 27th day of different months and attracted my attention as I researched World War II and the dire fate of European Jewry. Having embarked upon these studies for my book – Crossing the Borders of Time – about my mother’s family and their last-minute escape from Nazi-dominated France, I could not help but notice the recurrence of the number 27 throughout the history that was my focus. Why? Because while my mother is in every other respect a person devoid of superstition, a woman with little zeal for anything that smacks of mysticism or occult meanings, she has always harbored a dread fear of the number 27. It has seemed as if she thought that avoiding tragedy on the 27th might guarantee that every other day would be a good one.

Mom traces her targeted arithmophobia back to childhood. She claims that it was sparked by overhearing her mother denounce the number 27 as inherently ill omened, being the date that my great-grandfather, much beloved and far too young, died in Germany in 1913. In consequence of his early death, my mother never knew him. Yet so pervasive has been her fear that she actually pleaded with me to “hold on until midnight” when, years ago, I went into labor with my own daughter on a blessed July 27th in the early afternoon.

Given her experience in the Holocaust with the collective threat of lurking danger, my mother seizes on precautionary action to offer her some feeling of control. And so, ever wary of numerically induced disaster, she once fixedly refused to take her seat in a crowded airplane until my father found sympathetic fellow passengers willing to trade their “safer” seats for my parents’ 27A and B.

“You see those people seated in the 27th row?” Dad the rationalist pointed drily to the other couple, as the plane to California lifted from the runway. “I should warn you – if they go down, we go down also.”

Sensitized by a lifetime of such moments, I was alert to encountering the number as I delved into my mother’s story. The date, for instance, that France became the first European country to offer Jews full citizenship: September 27, 1791. The date the collaborationist Vichy government made it permissible to print racist attacks against Jews in the French press: August 27, 1940. The date that Germany signed a Tripartite Pact with Italy and Japan that aimed to keep America from joining in the war: September 27, 1940. That same day, the Nazis imposed the first anti-Jewish ordinance in the northern two-thirds of defeated France that the armistice permitted them to occupy with iron rule.

It was March 27, 1942, when the first German transport sent more than a thousand Jews from France to death at Auschwitz in Poland. On July 27, 1944, the Germans moved to crush the French Resistance and, gunning down five patriots, left their bloodied corpses as a warning sprawled upon a Lyon sidewalk. Four months later, on November 27, 1944, British bombers leveled the medieval German town of Freiburg, my mother’s birthplace and her home until her family, stripped of valuables and identity, fled across the Rhine to France.

My account of 27s could easily go on, but I do not permit myself to view them as anything but coincidence. All the same, I recognize that the yearning to consecrate events in memory arises naturally from the human heart. There is value in setting aside a day for Holocaust remembrance, be it the 27th of January or of Nissan: in honoring the millions lost we grant them a measure of immortality and affirm commitment to ensuring that such horrors never occur again. Indeed, as years go by, memorializing must drive action to end mass killings – whether the result of state-sponsored genocide or the carnage wrought by troubled individuals allowed to arm themselves with lethal weapons in their wars against the world.

Only by turning every day into a day of memory can we begin to stem the sort of senseless violence that makes each of us a potential mourner or a victim. Surely, if alerted to the frightful import of a number other than 27, we would find reasons justified by history to record its fatefulness. Twenty blameless children executed in their classrooms in Connecticut. A young woman tortured, raped, and murdered in New Delhi. A man shoved onto the New York City subway tracks to die beneath a speeding train. The randomness of evil supports no explanation. Our efforts to mark its madness in time underline our yearnings to delimit it. But beyond setting dates apart on calendars, we must use our grief about the past to trigger change.

Lovely post. Thank you for sharing.